25-8 News Network

Wednesday, December 15, 2010

Monday, December 6, 2010

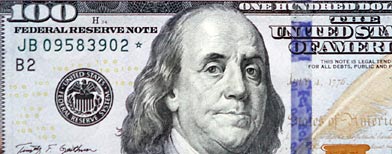

Government's 110 billion dollar printing mistake.

Originally posted on Yahoo News

By Zachary Roth zachary Roth – Mon Dec 6, 9:36 am ET

As a metaphor for our troubled economic and financial era -- and the government's stumbling response -- this one's hard to beat. You can't stimulate the economy via the money supply, after all, if you can't print the money correctly.

Because of a problem with the presses, the federal government has shut down production of its flashy new $100 bills, and has quarantined more than 1 billion of them -- more than 10 percent of all existing U.S. cash -- in a vault in Fort Worth, Texas, reports CNBC.

"There is something drastically wrong here," one source told CNBC. "The frustration level is off the charts."

[Related: Money fair showcases $100,000 bill]

Officials with the Treasury and the Federal Reserve had touted the new bills' sophisticated security features that were 10 years in the making, including a 3-D security strip and a color-shifting image of a bell, designed to foil counterfeiters. But it turns out the bills are so high-tech that the presses can't handle the printing job.

More than 1 billion unusable bills have been printed. Some of the bills creased during production, creating a blank space on the paper, one official told CNBC. Because correctly printed bills are mixed in with the flawed ones, even the ones printed to the correct design specs can't be used until they 're sorted. It would take an estimated 20 to 30 years to weed out the defective bills by hand, but a mechanized system is expected to get the job done in about a year.

[Related: Design firm seeks to rebrand dollar with Obama's image]

Combined, the quarantined bills add up to $110 billion -- more than 10 percent of the entire U.S. cash supply, which now stands at around $930 billion.

The flawed bills, which cost around $120 million to print, will have to burned.

The new bills are the first to include Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner's signature. In order to prevent a shortfall,the government has ordered production of the old design, which includes the signature of Bush administration Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson. That, surely, is not the only respect in which the nation's lead economic officials would like to turn back the clock to sometime before the 2008 financial crisis.

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

Clear 4G Rip-off ?

Has Clearwire/Clear ripped you off? Here are some people that has and bone to pick with Clear's supposed 4g internet service.

THEY MAKE IT SIMPLE MY ASS…. – User Submission by Bob F.

December 1st, 2010

I am not the most experienced computer person…I’m a bit older and bought a MacBook because it is a much easier computer…however…Clearwire or Clear…whatever…has made it difficult to maintain a connection…and when I call customer service they are less than helpful…one even offered to talk slower because I was older…if he had been right in front of me I would have hit him…

I still can’t maintain a good connection and the damn thing is aimed right at the tower…I asked if technician could come out to look at my set-up and help…their response was no…

Now how could we be in a bad economy if these fools don’t value their customers? Once again they will take money out of my account and I don’t have service…very nice…

Bob F

And there is alot more check here at

Please send us an E-mail with your experience, and have it featured on the main page!

Help us educate others on the true side of Clearwire!

Visit the User Forums and join in a discussion! / Follow us on Twitter! / Contact Legal Representative

Lawsuit Filed Against CLEARWIRE! / Submit your story!

Here

4G Myth

chart_is_it_4g_v2.top.gif By David Goldman, staff writerDecember 1, 2010: 9:14 AM ET

NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- You've seen the 4G advertisements from T-Mobile, Sprint and Verizon, bragging about a much-better wireless network with blazing fast speeds.

Here's the secret the carriers don't advertise: 4G is a myth. Like the unicorn, it hasn't been spotted anywhere in the wild just yet -- and won't be any time in the near future.

The International Telecommunication Union, the global wireless standards-setting organization, determined last month that 4G is defined as a network capable of download speeds of 100 megabits per second (Mbps). That's fast enough to download an average high-definition movie in about three minutes.

None of the new networks the carriers are rolling out meet that standard.

Sprint (S, Fortune 500) was the first to launch a network called 4G, going live with it earlier this year. Then, T-Mobile launched its 4G network, claiming to be "America's largest 4G network." Verizon (VZ, Fortune 500) plans to launch its 4G network by the end of the year, which it claims will be the nation's largest and the fastest. AT&T (T, Fortune 500) is expected to unveil its 4G network next year.

Those networks have theoretical speeds of a fifth to a half that of the official 4G standard. The actual speeds the carriers say they'll achieve are just a tenth of "real" 4G.

So why are the carriers calling these networks 4G?

It's mostly a matter of PR, industry experts say. Explaining what the wireless carriers' new networks should be called, and what they'll be capable of, is a confusing mess.

To illustrate: Sprint bought a majority stake in Clearwire (CLWR), which uses a new network technology called WiMAX that's capable of speeds ranging from 3 Mbps to 10 Mbps. That's a different technology from Verizon's new network, based on a standard called Long Term Evolution (LTE), which will average 5 Mbps to 12 Mbps.

Seeing what its competitors were up to, T-Mobile opted to increase the speed capabilities of its existing 3G-HSPA+ network instead of pursuing a new technology. Its expanded network -- now called 4G -- will reach speeds of 5 Mbps to 12 Mbps.

No matter what they're called, all of these upgrades are clear improvements -- and the carriers shelled out billions to make them. Current "3G" networks offer actual speeds that range from between 500 kilobits per second to 1.5 Mbps.

So Sprint and Verizon have new, faster networks that are still technically not 4G, while T-Mobile has an old, though still faster network that is actually based on 3G technology.

Confused yet? That's why they all just opted to call themselves "4G."

The carriers get defensive about the topic.

"It's very misleading to make a decision about what's 4G based on speed alone," said Stephanie Vinge-Walsh, spokeswoman for Sprint Nextel. "It is a challenge we face in an extremely competitive industry."

T-Mobile did not respond to a request for comment.

0:00 /0:55Sprint's 4G challenges iPhone

One network representative, who asked not to be identified, claimed that ITU's 4G line-in-the-sand is being misconstrued. The organization previously approved the use of the term "4G" for Sprint's WiMAX and Verizon's LTE networks, he said -- though not for T-Mobile's HSPA+ network.

ITU's PR department ignored that approval in its recent statement about how future wireless technologies would be measured, the representative said. ITU representatives were not immediately available for comment.

"I'm not getting into a technical debate," said Jeffrey Nelson, spokesman for Verizon Wireless. "Consumers will quickly realize that there's really a difference between the capabilities of various wireless data networks. All '4G' is not the same."

And that's what's so difficult. The term 4G has become meaningless and confusing as hell for wireless customers.

For instance, T-Mobile's 4G network, which is technically 3G, will have speeds that are at least equal to -- and possibly faster -- than Verizon's 4G-LTE network at launch. At the same time, AT&T's 3G network, which is also being scaled up like T-Mobile's, is not being labeled "4G."

That's why some industry experts predict that the term "4G" will soon vanish.

"The labeling of wireless broadband based on technical jargon is likely to fade away in 2011," said Dan Hays, partner at industry consultancy PRTM. "That will be good news for the consumer. Comparing carriers based on their network coverage and speed will give them more facts to make more informed decisions."

Hays expects that independent researchers -- or the Federal Communications Commission -- will step in next year to perform speed and coverage tests.

Meanwhile, don't expect anyone to hold the carriers' feet to the fire.

"Historically, ITU's classification system has not held a great degree of water and has not been used to enforce branding," Hays said. "Everyone started off declaring themselves to be 4G long before the official decision on labeling was made. The ITU was three to four years too late to make an meaningful impact on the industry's use of the term." To top of page

Google gives Groupon a $6 Billion offer

Originally posted on Forbes.com

Everybody in the tech business has a friend or a friend of a friend who sold out for several million. Yapping about the prolific growth of startups gone by makes for easy–but banal–cocktail banter. Then there’s Groupon, a company that’s been around for two years and could reportedly fetch $6 billion from Google. Now that’s a story worth dissecting over a single malt.

There’s no need to rehash Groupon’s business model here, but for those who are curious, we dubbed Groupon the fastest growing company ever in an August cover story.

Prescient Cover

The company’s profile has exploded since then, but Groupon hardly needed help from us. An April capital raise had valued the company at $1.35 billion when it was a mere 17 months old.

If Google indeed pays $5-$6 billion for Groupon, it will likely be shelling out at least six times revenues for the company. That’s not a zany valuation for a two-year-old startup. Happens all the time. But for a company that’s already at $1 billion in revenue? That does not happen all of time. In fact, it just doesn’t happen. Ever.

The Wall Street Journal reports that Groupon’s board is discussing Google’s offer right now. What’s to discuss? Apparently there are parties inside Groupon who think an IPO may be a wiser play. And we know investment banks–including Morgan Stanley–have been jockeying for underwriting opportunities with Groupon for at least a year.

The fact that Groupon has options–good ones–explains the size of Google’s bid.

Groupon has fashioned a nifty borehole straight into the marketing budgets of small businesses all over the country (and planet). Google has had difficulty cracking exactly these prospects. Same with everybody else out there. Groupon’s name carries weight with these merchants and its sales force, while certainly something Google could build on its own, can’t be put together overnight.

Groupon realizes its opportunity. The board will take its time. Andrew Mason and Eric Lefkofsky are two men who have never been aiming small. That’s been clear since the first time I met Andrew three years ago, pre-Groupon. It’s a fact that was reinforced when Groupon brushed off Yahoo’s earlier offer to buy it for a reported $3 billion. That sale would have launched Lefkofsky, the largest Groupon equity holder, to billionaire status.

Now, both Lefkofsky and Mason stand to become billionaires.

No matter what happens, the other clear winner here, beyond Groupon, is the tech community of Chicago. The city is a magnet for graduates of nearby top-notch computer science programs, but has never gained a shadow of the traction enjoyed by Silicon Valley or Boston. Lots of good ideas spring from Chicago and the area (Netscape, one of the first dominoes of this Web saga, was kindled at the University of Illinois), but those companies usually bee-line to California.

A $6 billion infusion from Google would enrich lots of Groupon Chicagoans. The best thing for Chicago, of course, would be a kind of Groupon mafia who could spawn new area tech companies and investments the way progeny from Google, Facebook, PayPal and others have done in the Valley.

The term mafia has been used to describe exactly this effect before, especially when it comes to PayPal and now Y Combinator, but nowhere will it be as ironic–or as important to its city–as a new mafia would be in Chicago.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)